In 2018 in the United States, homelessness and poverty have been increasing over the years. Wages remain low or flat for most people, cost of living is increasing, rents are skyrocketing as well as property values due to a speculative market on real estate and land.

At the same time federal funding for public non-profit housing development is weak. This has all added up to what we see in the country today with the lack of affordable housing. When housing isn’t available or affordable, people fall through the cracks, and this leads to increased homelessness.

To successfully solve this problem today requires us to first look back at the history of public housing in the US to see how we got to this point and present some examples of housing models which might be achievable under current legal and systemic constraints.

Public housing in the United States is administered by federal, state and local agencies to provide assistance for low-income households. Public housing is priced well below the market rate. It is provided in various settings and formats.

Originally public housing in the U.S. consisted primarily of one or more concentrated blocks of low-rise and/or high-rise apartment buildings. These complexes are operated by state and local housing authorities which are authorized and funded by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. More than 1.2 million households currently live in public housing of some kind.

Subsidized apartment buildings, often referred to as housing projects, have a complicated history in the United States. While the first decades of projects were built with higher construction standards and a broader range of incomes and applicants, over time, public housing became the housing of last resort in many cities.

Several negative stereotypes associated with public housing create difficulties in developing new units. Perceptions of public housing include some major public concerns: a lack of maintenance, expectation of crime, disapproval of housing as a handout, reduction of property values, concentration of poverty, increased crime and physical unattractiveness. While the reality may differ from the perceptions, such perceptions are strong enough to mount formidable opposition to public housing programs in general over the years.

Several reasons for these stereotypes include the failure of Congress to provide sufficient funding, lowering of standards for occupancy, as well as government mismanagement at the local level.

Permanent, federally funded housing came into being in the United States as a part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Title II, Section 202 of the National Industrial Recovery Act, passed June 16, 1933, directed the Public Works Administration to develop a program for the construction, reconstruction, alteration, or repair of low-cost housing and slum clearance projects. The initial, Limited-Dividend Program aimed to provide low-interest loans to public or private groups to fund the construction of low-income housing. Too few qualified applicants stepped forward, and as a result, the Limited-Dividend Program funded only seven housing projects nationally.

In the spring of 1934, the Housing Division began to undertake the direct construction of public housing, a decisive decision that would serve as a precedent for the 1937 Wagner-Steagall Housing Act which set the template for public housing in the United States at the time. By 1937, the Housing Division had constructed fifty-two housing projects across the United States including Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

Based on the residential planning concepts of these fifty-two projects composed of one to four story row house and apartment buildings, arranged around open spaces, creating traffic-free community spaces between units. Many of these projects were built on slum land, but land acquisition proved difficult, so abandoned industrial sites and vacant land were also purchased.

The FHA institutionalized a practice by which it would seek to maintain racially homogeneous neighborhoods, although this practice was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1948 and outlawed by legislation in 1960. Many white residents in Detroit in the 1940’s strongly protested the creation of new public housing units. When their protests did not help, they left for the suburbs, so-called “white flight”.

In 1937, the Wagner-Steagall Housing Act replaced the temporary PWA Housing Division with a permanent, quasi-autonomous agency to administer housing. The United States Housing Authority Act of 1937 would operate with a strong focus towards local efforts in locating and constructing housing and would place caps of $5000 spent per housing unit. Construction of housing projects dramatically accelerated under the new structure. In 1939 alone, 50,000 housing units were constructed, more than twice as many as were built during the entire tenure of the Public Wors Authority Housing Division.

During World War 2, entire communities sprang up around factories that manufactured military goods. In 1940, Congress authorized the US Housing Authority to build twenty public housing developments around these private companies to sustain the war effort. The Defense Housing Division was founded in 1941 and would ultimately construct eight developments of temporary housing. Many became long-term housing units after the war.

During World War II, construction of homes dramatically decreased as all efforts were directed towards the War. When the veterans returned from overseas, they came ready to start a new life, often with families, and did so with the funding resources of the G.I. Bill to get a new mortgage. However, there was not enough housing to accommodate demand. Efforts moved to focus exclusively on veterans housing, specifically a subsidy on materials for housing construction. However, in the wake of the 1946 elections, President Truman believed there was insufficient public support to continue materials subsidies. The Veterans’ Emergency Housing Program ended on January 1947 by an executive order from President Truman.

Unhappiness with Urban Renewal policies came quick after the passage of the bill. Urban renewal had become, for many cities, a way to eliminate blight, but not a solid vehicle for constructing new housing. For example, in the ten years after the bill was passed, 425,000 units of housing were demolished, but only 125,000 units were constructed.

No major legislation changed the basic mechanisms of public housing until the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965.

This act created the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), a cabinet-level agency to address housing. The act also introduced rent subsidies for the first time, shifting a trend towards privately constructed low-income housing. With this legislation, the Federal Housing Authority would insure mortgages for non-profits which would then construct homes for low-income families. HUD could then provide subsidies to bridge the gap between the cost of these units and a set percentage of a household’s income.

In response to many of the emerging concerns regarding new public housing developments, the Housing Act of 1968 attempted to shift the style of housing developments. The act banned the construction of high-rise developments for families with children. Rising rates of vandalism and vacancy and with concerns about the concentration of poverty, these developments were declared unsuitable for families.

Section 235 of the Housing Act of 1968 encouraged white flight from the inner city by selling suburban properties to whites and inner-city properties to blacks, thus creating neighborhoods that were racially isolated from other neighborhoods. Public housing units were often built in predominantly poor and black areas, reinforcing racial and economic differences and stereotypes between neighborhoods.

Scattered Site Housing (1969 – Present)

Alternative models such as scattered-site housing in which the housing is publicly funded, affordable, and low-density units that are scattered throughout diverse, middle-class neighborhoods. The class-action case that led to the popularization of scattered-site models was Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority in 1969.

The lawsuit was resolved with a verdict mandating that the Chicago Housing Authority redistribute public housing into areas less than 30% black for every one unit built in areas that were more than 30% black.

Scattered-site housing programs are generally run by the city housing authorities or local governments. Many scattered-site units are built to be similar in appearance to other homes in the neighborhood to somewhat mask the financial stature of tenants and reduce the stigma associated with public housing. Scattered-site housing programs became popularized in the late 1970s and 1980s. Since that time, cities across the country have implemented such programs with varying levels of success.

Vouchers, initially introduced in 1965, were an attempt to subsidize the demand side of the housing market rather than the supply side by supplementing a household’s rent allowance until they were able to afford rent at market rates. The program had the effect of tightening the market for low-income housing, and communities were in need of an infusion of additional units.

In 1973, President Richard Nixon halted funding for numerous housing projects in the wake of concerns regarding the housing projects constructed in the prior two decades. The ban was lifted in the summer of 1974, as Nixon faced impeachment in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

The Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 created the Section 8 Housing Program to encourage the private sector to construct affordable homes. This kind of housing assistance assists poor tenants by giving a monthly subsidy to their landlords. This assistance can be ‘project based,’ which applies to specific properties, or ‘tenant based,’ which provides tenants with a voucher they can use anywhere vouchers are accepted. Tenant based housing vouchers covered the gap between 25% of a household’s income and established fair market rent. Virtually no new project based Section 8 housing has been produced since 1983, but tenant based vouchers are now the primary mechanism of assisted housing.

Changes to public housing programs were minor during the 1980’s. Under the Reagan administration, household contribution towards Section 8 rents was increased to 30% of household income, and fair market rents were lowered. Public assistance for housing efforts however was reduced as part of a package of across the board cuts. Additionally, policies resulted in the expansion of emergency shelters for the homeless rather than permanent housing.

More people became homeless as well after the passage of the 1981 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act which cut funding for mental health facilities. This pushed the responsibility of mentally ill patients back to the states. After patients were released from mental hospitals, there wasn’t always a place for them to go. This resulted not only in increased homelessness, but also a more mentally unstable homeless population overall.

The next era in public housing began in 1992 with the launch of the HOPE VI program. HOPE VI funds were devoted to demolishing poor-quality public housing projects and replacing them with lower-density developments, often of mixed-income. HOPE VI became the primary vehicle for the construction of new federally subsidized units, but it suffered considerable funding cuts in 2004 under President George W. Bush.

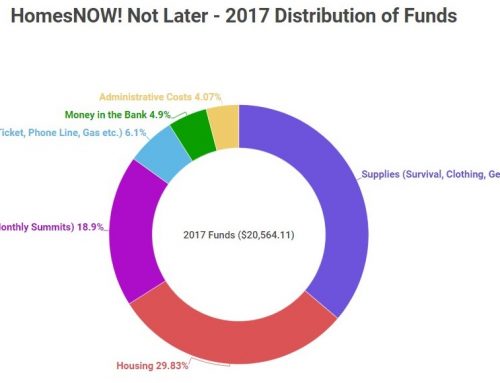

There have been no significant reforms implemented since but the problem still remains and continues to get worse due to budget cuts to fund housing. This means the community has had to step up to the plate without public funds to make progress on affordable housing for those in need where public institutions have failed to address the shortfall in available housing.

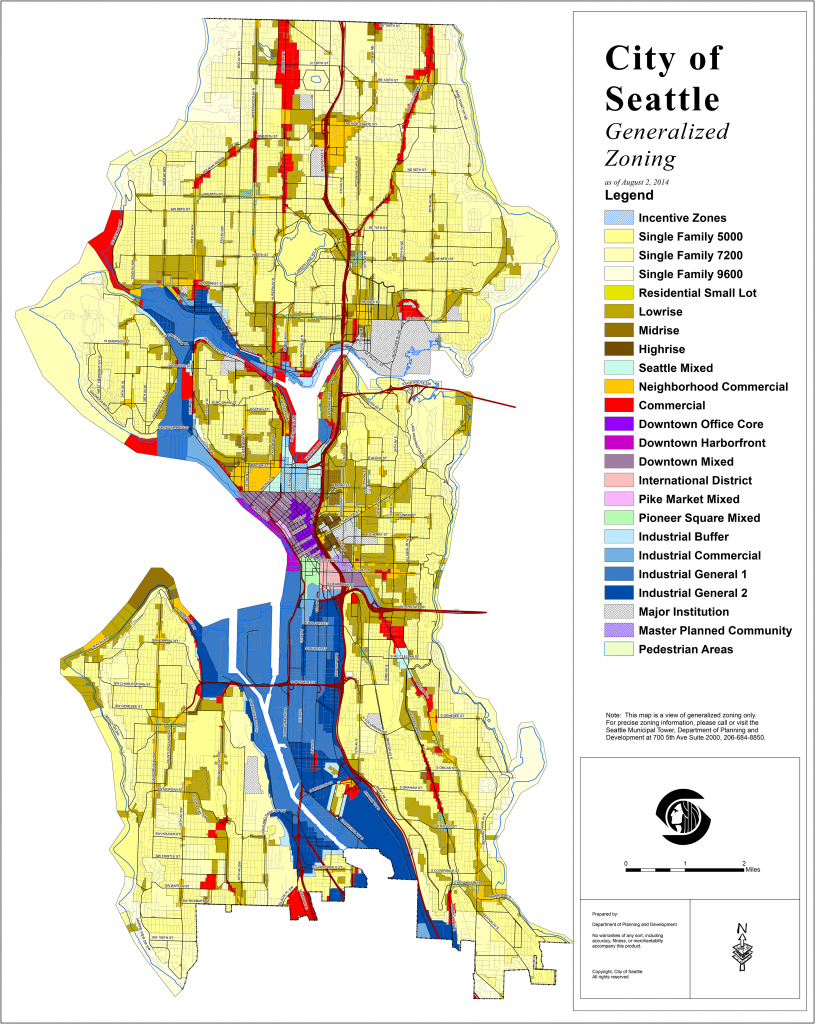

This has resulted in the emergence of semi-permanent homeless tent encampments and increased popularity of Tiny Homes. Even though tiny homes are low-cost and have a low impact on the environment, most city’s zoning laws make it difficult to develop a tiny home community even if you have the land.

For example many cities will zone their land to be single-residential in most areas, which means that you can only have a few unrelated people living on the same piece of land (usually a maximum of 3). This paradoxially means that if one is trying to build a tiny home community, they wont be able to do so in a residential area, even though it’s meant to be a place where residents live.

In order to solve the housing problem without the use of government funding, cities and counties could benefit from changing their zoning to be more favorable to building affordable non-profit housing, either through tiny homes or apartments.

Hopefully city, county and state governments will be able to adapt to allow the the problem of affordable housing to be solved. Unfortunately as long as land and real estate is a speculative market, the chances of that seem unlikely. Affordable housing development doesn’t bring money into the coffers of local governments, therefore it is set aside in favor of more lucrative development, but this ends up leaving many individuals behind.

One can only hope that the attitudes and stereotypes around public housing and homelessness can be shattered so that real progress can actually be made to solve this vital issue.

Sources:

Public housing in the United States:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_housing_in_the_United_States

New York City’s Public-Housing Crisis:

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/05/new-york-citys-public-housing-crisis/393644/

The Impacts of Affordable Housing on Education: A Research Summary:

http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/19cfbe_c1919d4c2bdf40929852291a57e5246f.pdf

Section 8 Rental Certificate Program:

https://www.hud.gov/programdescription/cert8

Washington’s Grand Experiment to Rehouse the Poor:

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/21/us/21housing.html

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development:

https://www.hud.gov/

The History of Public Housing: Started over 70 Years Ago, yet Still Evolving:

https://www.socialworkhelper.com/2013/02/04/the-history-of-public-housing-started-over-70-years-ago-yet-still-evolving/